The making of Grendizer

Creating Grendizer gave me the deepest pleasure and

emotion: it doesn't happen every day to have the chance to bring to (virtual!)

life with your hands one of the greatest myth of fantasy of your childhood and,

above all, to make of it your personal and exclusive toy. Grendizer will always

be to me the "prince" of all the Super Robots: a mighty prototype

compared to whom the other steel heroes appear to belong to a lesser rank.

Grendizer is a classic, while the others a enjoyable characters.

During modeling, I've learned at my expense the hardness

of the problem of "translating" something that has always lived a 2D

existence into a tridimensional version capable of preserving a full

compatibility with the perspectives of the "flat" model: whatever the

solutions and the choices made along the work, the imperative requisite of the

final result had to be total adherence to all the spectacular images

of this powerful robot in action. Compromises, too personal interpretations,

attempts to privilege only a limited number aspects would have inevitably

turned into a burning delusion, vanishing the meaningfulness of using the 3D

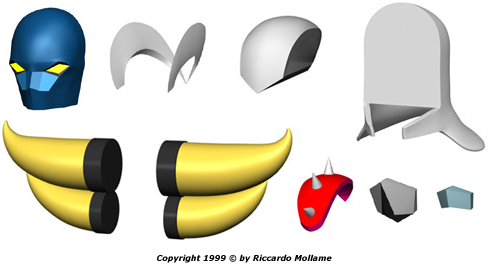

techniques. No need to say that Grendizer's head has taken away the greatest

amount of time and energies, especially what I call the "helmet": yet

using a powerful tool like patch in conjunction with metaform, only after tens

and tens of attempts I've been able to produce a barely satisfactory

result.

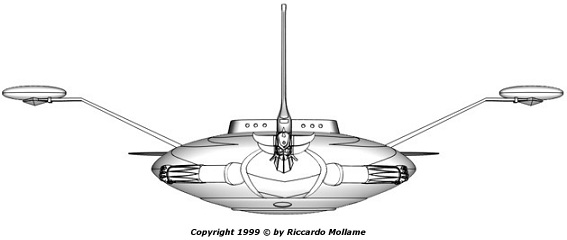

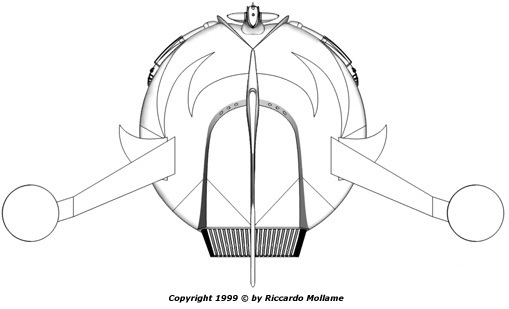

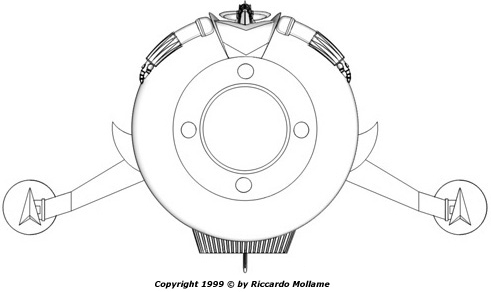

As far as I

could see, several structural inconsistencies, mostly negligible, yet

intrinsic, pop up during modeling. Away from numbering them all, I can't help

but mentioning the most macroscopic and already apparent simply watching the

scenes of the cartoon: the way Grendizer is hosted in his spaceship. No matter

how you could shape the disk's cross-section, there is absolutely no way on

earth to integrate Grendizer's body as seamlessly into the disk as he appears

in many classic pictures where, even, boomerang's blades that should adhere to

the chest, look like following the disk's profile once the robot is hosted

inside: moreover (and yet worse) arms are so smoothly bent around disk's

circumference to give the impression to be painted on it. Despite these nasty

critics, during modelling the saucer I've had the chance to appreciate the

remarkable consistency of proportions of the ensemble robot-disk shown in the

cartoons during fly scenes: rotating the object and watching it from a number

of perspectives, I've even reached the conclusion that people that were in

charge of Grendizer's animation had necessarily to work with a scale model to

keep that degree of coherence in reproducing disk's maneuvers and

close-ups.

Not

questioning the magnificence of Grendizer's lines, heavy critics could

nevertheless be raised about the mechanical realism of the robot. Legs and arms

for instance are nothing but straight cylinders, reducing elbows and knees to

tiny slots: a rigorous interpretations of these structures would prevent every

form of articulation. This drawback gave me not few problems when I had to

decide what poses to use for rendering: as someone could notice, I have avoided

when possible to include in the frame of the final picture a too direct detail

of the joints, while in some other pictures I resorted (I confess!) to stretch

and deform the edges of the parts involved to follow bendings and torsions as

much as possible: the unpleasant conclusion is that Grendizer is substantially

unsuitable to produce quality animations, at least if some degree coherence is

meant to be kept.